Featured Scientist: Nicole A. Campbell, M.S. 2019, School of Biological Sciences, Illinois State University

Birthplace: Joliet, IL

My Research: I am fascinated by the process of embryonic development. As an embryo develops, it is critical that the correct hormones are expressed at the right times to ensure that the embryo is healthy. My work focuses on embryos of the European starling, but my research can also help us to understand human systems. People used to think that hormones directly affect an embryo as it grows and develops, but this idea is at odds with what we know about how these hormones are broken down in the body. As an embryo grows, hormones are quickly processed through metabolism. With the help of my adviser Dr. Paitz, I examined a different idea: that the effects of hormones are driven by their metabolites.

Research Goals: I hope to continue research in the future by working with animal breeding programs to help endangered species.

Career Goals: I want to have a career where I can apply science to help breed and restore endangered animal species. I am hopeful that this work will help me transition to a career where I get to work directly with endangered species, like the red panda.

Hobbies: I love crafting cute projects that I find on Pinterest and managing my dog’s Instagram page.

Favorite Thing About Science: My favorite thing about science is being able to visually see things, like embryos, while they are developing. I get to see natural processes in person. It’s pretty amazing how something so small can contain all of the information about how an animal develops.

Organism of Study: European starling

Field of Study: Comparative Endocrinology

What is Comparative Endocrinology? Comparative Endocrinology is the study of hormones and their effects on various aspects of development in animals. My research uses animal models to test the effects of different hormones, which can inform us about their roles in the human body.

Check Out My Original Paper: “Characterizing the timing of yolk testosterone metabolism and the effects of etiocholanolone on development in avian eggs”

Citation: N.A. Campbell, R.A. Angles, R.M. Bowden, J.M Casto, R.T. Paitz, Characterizing the timing of yolk testosterone metabolism and the effects of etiocholanolone on development in avian eggs. J. Exp. Biol. 223.4: (2020).

Research at a Glance: When birds lay eggs, the yolk contains both hormones and nutrients for the developing embryo. In this paper, I investigated how starlings break down hormones in the egg. I also studied important metabolites of this breakdown and conducted tests to see if the metabolites affected embryonic growth.

It’s important to know how long specific hormones remain in an embryo. If we know how long a hormone is present, then we can determine whether or not it will influence the embryo. In this study, we looked at the hormone testosterone, to see how quickly it breaks down during early development in starling embryos. Surprisingly, we found that most of the testosterone is broken down within just a few hours. This result raised another question: how does testosterone affect the embryo if it is broken down so rapidly?

We guessed that testosterone may affect the embryo’s secondary metabolites. Secondary metabolites are the products that are made when hormones are broken down. Our work showed that these metabolites stick around inside the egg yolk much longer than testosterone. We set out to see if these metabolites affect the growth of the embryo. We injected extra amounts of a secondary metabolite, etiocholanolone, into the eggs. Our results did not show that extra etiocholanolone affected embryonic development. One explanation for our results is that there was already etiocholanolone present in the eggs.

Highlights: I think the most important step for my research is the study that we did on in ovo testosterone metabolism. We performed this experiment over the course of two laying seasons. In the first season, we gathered 38 freshly laid starling eggs from our study site and took eggs from 36 different clutches. We purchased a radiolabeled form of testosterone that would allow us to keep track of testosterone levels as the embryos grew. We injected each egg with testosterone mixed with sesame oil. The oil was used to keep the injection of the radiolabeled testosterone in one spot near the embryo. We did this so that the testosterone could diffuse from that central area into the embryo. Then, each egg was allowed to grow for different lengths of time in an incubator. The period of time that the eggs were allowed to grow was assigned randomly.

Next, we wanted to see what happened to the testosterone. We removed the eggs from the incubator, froze them, and separated the egg into two parts: the yolk and albumen. We weighed each part, then separated out the hormones. We were able to isolate the hormones using two techniques: solid phase extraction and column chromatography. Finally, we put the samples through a scintillation counter. The scintillation counter helped us test which metabolites had our radiolabel on them. By figuring out which metabolites had our radiolabel, we could tell how much of the testosterone we injected had broken down.

When we repeated this experiment in the second season, we used more testosterone for our injections and shortened the length of time that eggs were allowed to grow.

We sampled embryos within a 12-hour window. We also mixed the yolk with the albumen when we sampled and used a yolk/albumen mix to extract hormones. Our results show that after incubation starts, the testosterone in the egg breaks down quickly. This means that testosterone probably does not directly affect how the embryos develop. Instead, we think that the testosterone metabolites are responsible.

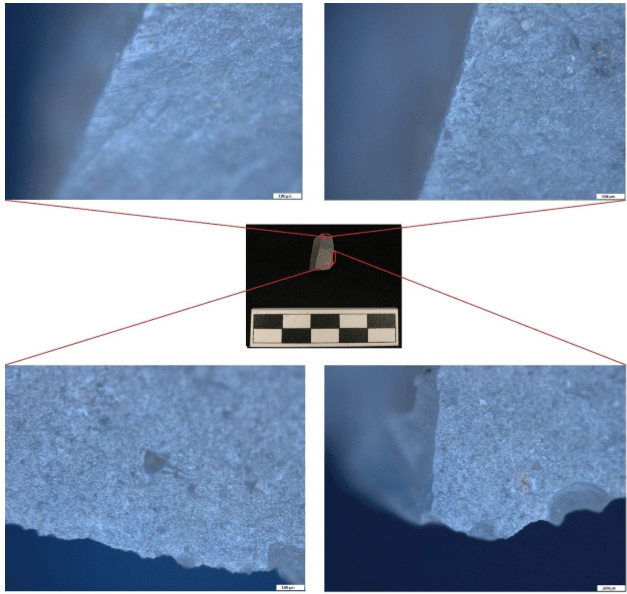

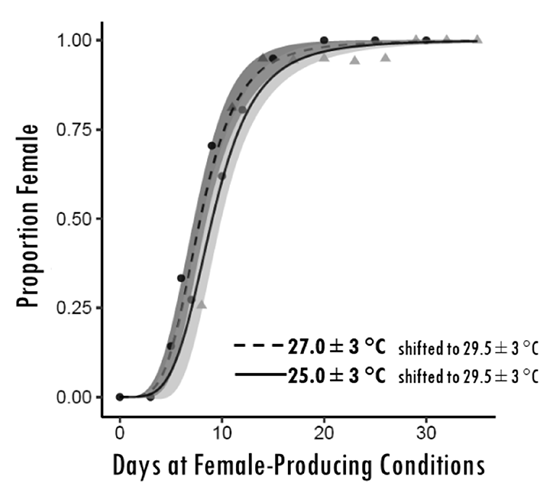

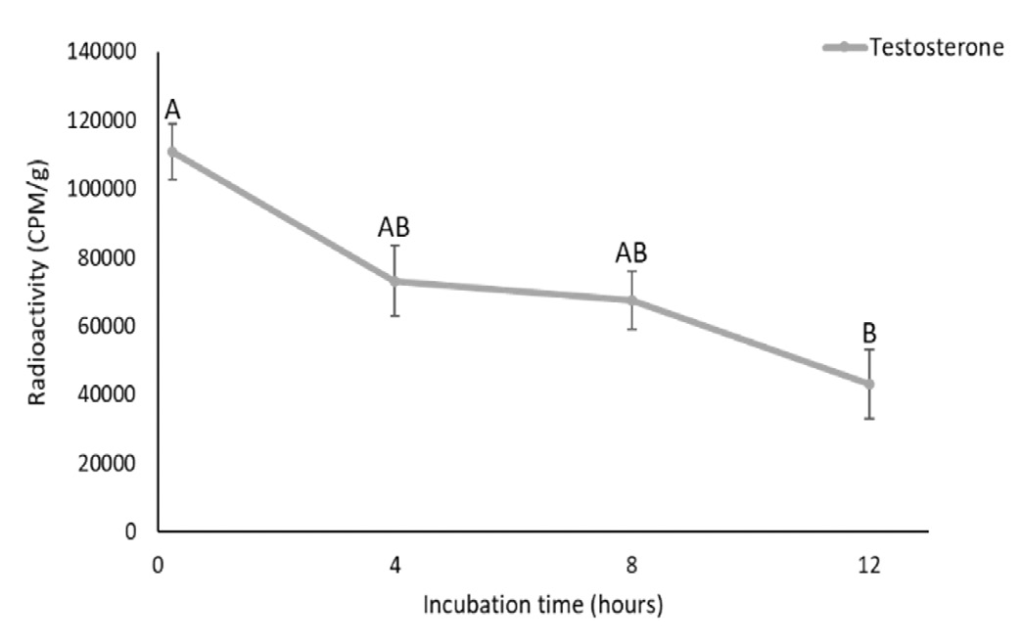

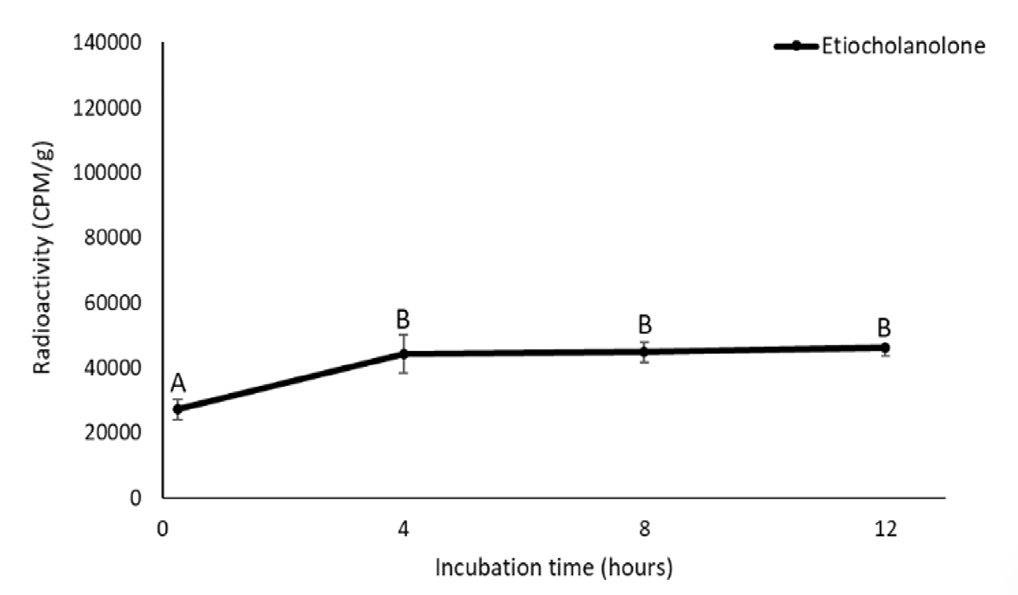

What My Science Looks Like: Figures 1-3 show the results of my experiment from the second season, where we added testosterone to the eggs and tracked how testosterone was broken down over the course of 12 hours. Each figure shows the average radioactivity on the y-axis. This tells us how much of the testosterone or metabolite is found in the yolk/ albumen mixture.

We looked at testosterone and two of its metabolites, androstenedione and etiocholanolone. In Figure 1, we see that the amount of testosterone in the eggs is rapidly dropping over time.

after 12 hours of incubation. Figure adapted from Campbell et al. 2020.

In Figure 2 and Figure 3, both androstenedione and etiocholanolone start to increase after only 4 hours of incubation. The fact that they both show up so early indicates that testosterone is being broken down quickly once the egg is incubated.

Figure 2. The amount of androstenedione, a testosterone metabolite, in the embryo after 12 hours of incubation. Figure adapted from Campbell et al. 2020.

Figure 3. The amount of etiocholanolone, a testosterone metabolite, in the embryo after 12 hours of incubation. Figure adapted from Campbell et al. 2020.

The Big Picture: We show that testosterone metabolites are present near the embryo before many key processes begin. We put forth the idea that testosterone itself may not be a major driver of developmental effects. Instead, testosterone metabolites may cause these effects. This type of research is important because it can tell us what may happen if normal hormone levels in early development are disturbed.

Decoding the Language:

Albumen: The white part of the egg that is water-soluble and that contains proteins.

Androstenedione: A hormone and metabolite of testosterone.

Clutch: A group of eggs that are laid at one time.

Column chromatography: A method used to isolate a single chemical compound from a mixture of compounds. Each compound moves through the column at different rates and this allows them to be separated.

Diffuse: To permit or cause to spread freely. In the context of this study, we wanted testosterone that was placed inside the egg to diffuse into a growing embryo.

Embryo: An unborn or unhatched offspring that is actively growing. In the context of this research, the embryo is the developing starling inside the egg.

Embryonic development: The process that takes place as an embryo grows and develops into an organism.

Etiocholanolone: A metabolite of testosterone.

Hormones: The signaling molecules that regulate the body and keep it in balance. These are produced by different glands within the body and are transported by the blood to target organs.

Incubation: The process of keeping an egg warm enough to develop until hatching.

Metabolites: The products of metabolism, or breakdown.

Radiolabel: A way to tag a substance or compound with a radioactive tag.

Scintillation counter: A machine that detects and measures the amount of radioactivity in a sample. It uses light pulses created by excited electrons or ions.

Solid phase extraction: A technique where compounds are suspended in a liquid mixture and are separated from other compounds in the mixture based on their physical and chemical properties.

Testosterone: A hormone that is important in the development of male secondary sex characteristics, but is also important in other body processes of both males and females.

Yolk: The yellow-orange, nutrient-rich portion of the egg that supplies food to the developing embryo.

Learn More: Below are some research papers for further reading.

C. Carere, J. Balthazart, Sexual versus individual differentiation: the controversial role of avian maternal hormones. Trends Endo. Metab., 18.2: 73–80 (2007).

N. Kumar, A. van Dam, H. Permentier, M. van Faassen, I. Kema, M. Gahr, T. G.G. Groothuis, Avian yolk androgens are metabolized instead of taken up by the embryo during the first days of incubation. J. Exper. Biol. 222.7 (2019).

R.T. Paitz, R.M.Bowden, J.M. Casto, Embryonic modulation of maternal Steroids in European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 278.1702: 99–106 (2011).

Synopsis edited by: Kate Evans, PhD (Anticipated Spring 2025) and Rosario Marroquin- Flores, PhD (Anticipated Spring 2022), School of Biological Sciences, Illinois State University.

Download this article here

Please take a survey to share your thoughts about the article!